Research Ethics Testi2023

-

A2. Introduction to Ethical Thinking

-

A2. Introduction to Ethical Thinking

This lecture gives you some idea of what ethics is and how it can be used to navigate through ethical challenges, questions and decisions in research practice. The lecture ends with a mandatory Reflective Activity assignment that everyone should submit.

The word ethics has multiple meanings for people in general and within the research community. First, ethics can be understood as standards of conduct, a set of norms and rules that define what we should or should not do, or what is right and what is wrong. In the research community we have Code of conduct that define what research misconduct is, for example. Also, researchers are required to follow certain ethical principles when their research involves human participants or animals.

Second, ethics is an academic discipline which studies standards of conduct and ethical decision-making. Academic ethics can be divided further to descriptive and normative ethics, and to theoretical and practical (applied) ethics. Descriptive ethics studies people’s ethical beliefs and attitudes. The empirical research questions of descriptive ethics are: What people believe they should do? What standards they hold ethical? And how their beliefs can be explained e.g., by psychological, neurobiological, religious, or sociological facts. The objective of normative ethics is different, however. It does not ask the empirical questions, but, instead, is concerned with normative questions: what standards of conduct ought to be, or what people ought to do (regardless of what they believe they should do).

Third, ethics can be viewed as a set of skills. Skills to make ethical decisions in situations in which one needs to specify what following the norm or ethical principle means in the specific situation, or in which several principles conflict. How to decide which of the conflicting principles should have priority or to find a balance between them? This capability to make ethically informed and justified decisions requires that one is able to recognize ethical aspects of the decision-making situation and how to weigh them against each other.

The next section introduces the main theories of normative ethics. The following section discusses how research ethics as a branch of practical ethics applies these theories to the conduct of research. Knowing ethical theories and how they are applied in research, helps you to understand how ethics applies to your research and how to make ethically informed choices when conducting your research.

Ethical theories

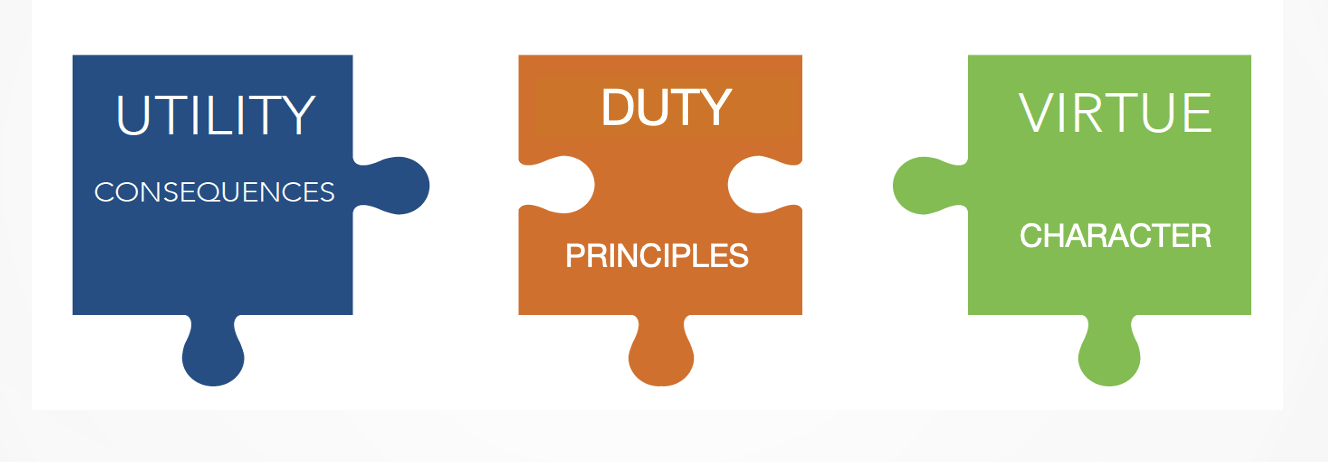

Theoretical ethics studies different theoretical ways to give reasons and justification for ethical conduct: what makes conduct morally required, permissible, or forbidden? Conventionally, the theoretical normative ethics is divided into three main approaches: consequentialism, deontology, and virtue ethics.

Each approach highlights a different and distinctive way to evaluate and justify ethical conduct. In consequentialist theories actions are evaluated solely by the outcomes or states of affairs they bring about. According to one of the most well-known consequentialist theory, utilitarianism, right conduct has outcomes that maximise welfare. Welfarist utilitarianism is a widely used approach in the Western social decision-making from budgets to health care decisions so many of us are very familiar with this approach. But utilitarianism is only one type of consequentialism. In pluralist consequentialist theories, there can be multiple values, in addition to welfare, that make outcomes good. For instance, fairness of the outcome might be one such value, and then the morally right action should bring about fair distribution of maximal welfare. Consequentialist theories therefore need to have a value theory which tells what makes action’s consequences good or bad, and if there are plural values, a theory should say how we should balance different values against each other: Should we always prioritise fairness over welfare when assessing the outcomes? Should we, for instance, aim to fair distribution even when it means that everyone’s welfare is levelled down and no-one’s welfare is improved?Deontological theories can claim to be able to avoid such trade-offs, since according to them moral rightness of a conduct is not (at least solely) based on the goodness of the outcomes it brings about. Rather the rightness is based on some moral norms, duties or principles, that require us to act in certain way regardless of the consequences. Think of a classic example against utilitarianism: If a doctor could save five people from death by killing one of her patients and using that patient’s organs for life-saving transplants, then utilitarianism that requires us to maximise welfare implies that the doctor should kill her patient to save five. But surely it seems clear to us that there is something terribly wrong in this way of sacrificing a life of one patient for the sake of greater overall welfare of other people. And we would hold this view, even if the patient who would be sacrificed without her consent would be terminally ill and would die soon anyway.

Deontological theories thus highlight the ethical constraints to consequentialist ethics even if they would not wholly deny the importance of good consequences (Also, there are several ways how so-called rule-consequentialists have attempted to justify these constraints in their own theory, e.g., by trying to show that these constraints if followed bring about the best outcomes). Moreover, deontological theories are agent-relative rather than agent-neutral. This means that the moral reasons are not the same to all, in all circumstances, like in agent-neutral consequentialism which gives the same reason of promoting the goodness of the outcomes to all. Deontology emphasises that different people in different situations have different moral reasons that cannot be overridden by overall good outcomes. The doctor in the example above has a specific duty to protect the life and wellbeing of her patient, even if the patient would die soon.

Justification for deontological principles and constraints can be based, for instance, on Categorical Imperative, formulated famously by Immanuel Kant (1724–1804). One formulation of the Categorical Imperative says that we should never treat other persons as a means only but always as an end in itself. Right-based views of ethics understand basic rights as a way to respect all persons as ends in themselves and protect them from being used only as a means to bring about good outcomes. Another formulation of Categorical Imperative highlights the autonomy of persons as a source of moral norms. This has been later understood, for instance, in contractualist way, that is, the right moral principles are those that autonomous people would in suitably constructed choice situation agree on (e.g., John Rawls’s famous hypothetical contract situation behind the veil of ignorance where people do not know their social positions which normally bias their choice of the principles). The autonomy formulation also stresses the importance of the central research ethical principle: respect of the autonomy of research subjects.

In contrast to consequentialism and deontology which evaluate morality of actions, virtue ethics focuses on developing good character traits, virtues. The key insight of virtue ethics is that ethical conduct is about acting in accordance with virtues. Some frequently mentioned virtues, such as honesty, honor, loyalty, benevolence, fairness, carefulness, are also character traits of good researchers. But knowing what the virtues are and possessing them is not enough, since sometimes being too honest in every situation, for instance, might not be what a virtuous person would do. One also needs to understand what being virtuous means in each situation and for that we need to acquire practical wisdom. Virtue ethics thus emphasises how important it is to understand ethical aspects of each situation, recognise the aspects that are more important than others. Thus, practical wisdom is a skill that also consequentialists and deontologists appreciate, since ability to apply ethical principles in concrete situations is a central part of ethics in many areas of life, including research ethics.

Research Ethics as applied ethics

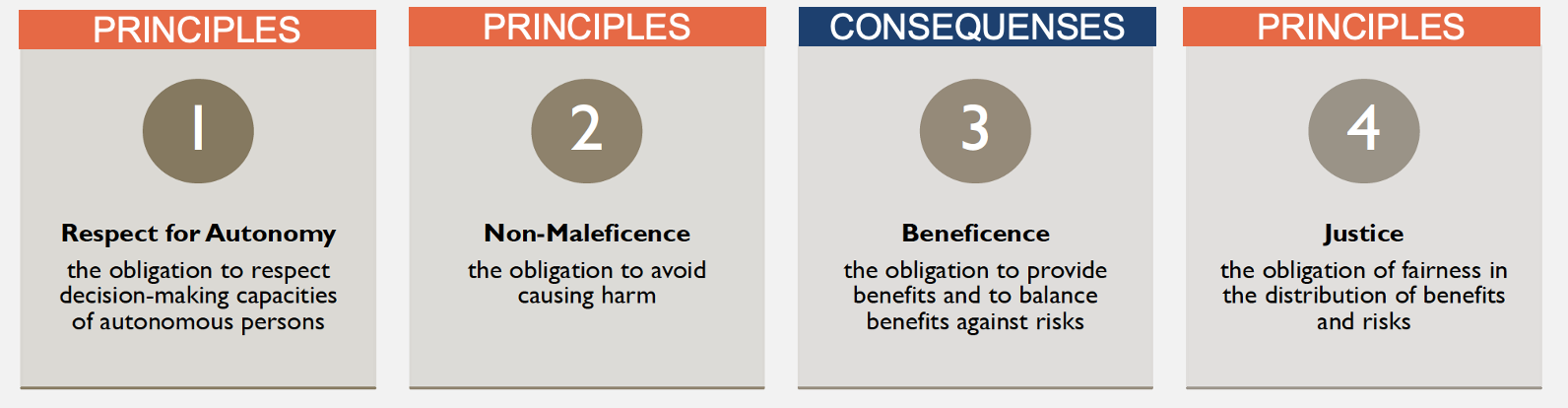

Research ethics is a branch of practical or applied ethics that applies above mentioned ethical theories and principles to the conduct of research. In research ethics the aspects of each theory are incorporated in several research ethical principles. For instance, in their classic presentation of Principles of Biomedical Ethics (first published in1983) Tom Beauchamp and James Childress introduce four main principles:

Even if these principles were formulated as fundamental principles of (bio)medicine, they are equally applied in other research fields today. The Respect for Autonomy grounds for instance the general research ethical principle of informed consent to participate in research. All research needs also to justify the potential harm (physical, mental, social, or economical) they cause to the research participants and others by the benefits research produces (new knowledge, better treatment of future patients, improved welfare, etc) (Beneficence) and consider how fairly the benefits and potential harms are distributed in the society (Justice). At the same time any research must avoid causing unnecessary and unreasonable harm to anyone (Nonmaleficence).

Additionally, The European Code of Conduct of Research Integrity defines general ethical principles to all research:

- Reliability in ensuring the quality of research, reflected in the design, the methodology, the analysis and the use of resources.

- Honesty in developing, undertaking, reviewing, reporting and communicating research in a transparent, fair, full and unbiased way.

- Respect for colleagues, research participants, society, ecosystems, cultural heritage and the environment.

- Accountability for the research from idea to publication, for its management and organisation, for training, supervision and mentoring, and for its wider impacts.

It is important to note, that all these principles are thought to be so-called prima facie ethical principles, which means they are always binding unless a stronger duty overrides or outweighs it. The prima facie nature of research ethical principles highlights again researchers’ capability to weigh the moral importance of different principles and when they conflict, to prioritise them in light of the relevant ethical features of the situation.

Research integrity can, moreover, be understood in two different ways, as Adil Shamoo and David Resnik (2015, 15) note:

According to the rule-following sense, to act with integrity is to act according to rules or principles. Integrity in science is a matter of understanding and obeying the different legal, ethical, professional, and institutional rules that apply to one’s conduct. Actions that do not comply with the rules of science threaten the integrity of research. According to the virtue approach, integrity is a kind of meta-virtue: We have the virtue of integrity insofar as our character traits, beliefs, decisions, and actions form a coherent, consistent whole. If we have integrity, our actions reflect our beliefs and attitudes; we “talk the talk” and “walk the walk”.

Both senses of integrity – rule-following and virtue approach – play an important role in the way how research ethics is discussed in this online course. This online course will refer to the ethical rules and principles throughout. One of the outcomes for the course will be an increased, and hopefully more coherent, understanding of the central ethical values and principles in the research community, why these values and principles are important and how they reflect on your research work.

Researchers’ capability to apply ethics

This short lecture invites you think through ethics, to consider which ethical principles guide your decision-making. The ethical thinking process typically incorporates at least the following elements.- Firstly, we need to identify that we are dealing with an ethical question. This invites us to incorporate values and norms in our decision making.

- Secondly, ethical decision-making seeks to identify the potential stakeholders of your decision, who are those potentially influencing your choices as a researcher or are affected by your research (e.g., benefitted or harmed). There is a lecture in the planning section titled Research context which deals more specifically with the stakeholder aspects.

- Good ethical thinking considers the rules and responsibilities that are relevant in the situation. What ethical principles apply in the situation and how they should be weighed against each other if they conflict? As highlighted earlier, ethical decisions are typically richly contextual - what is right or wrong, acceptable or not depends in many cases on the situation and the details of it, so it is essential to gain deep and rich understanding of a situation while making an ethical decision.

References:

Beauchamp, T.L. & Childress, J.F. (1983/2001) Principles of Biomedical Ethics. Oxford University Press.

Shamoo, A.E. &Resnik D.B. (2015) Responsible Conduct of Research. Oxford University Press.

Let’s look at these through a case study. Go to the Reflective Activity below, read the case study and submit your short answers:

A2. MANDATORY Reflective Activity - Thinking through ethics

Resources:

- More on ethical theory in research ethics: European Text Book on Ethics in Research (pp. 22-30)

- Ethics- from Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy (extensive introductory text)

- Consequentalism - from Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy (extensive text)

- Deontologism ("rule-based") - from Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (extensive entry)

- Virtue Ethics - from Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy (extensive text)

-